Hosni Mubarak is a dictator, despite whatever a clueless vice president says. But while he may be an S.O.B, he’s our S.O.B., and it could be that the interests of the U.S. diverge from the interests of the Egyptian people. Certainly if Mubarak gets replaced by a Sunni version of Iran’s Islamic theocracy, that would be A Bad Thing.

Hosni Mubarak is a dictator, despite whatever a clueless vice president says. But while he may be an S.O.B, he’s our S.O.B., and it could be that the interests of the U.S. diverge from the interests of the Egyptian people. Certainly if Mubarak gets replaced by a Sunni version of Iran’s Islamic theocracy, that would be A Bad Thing.

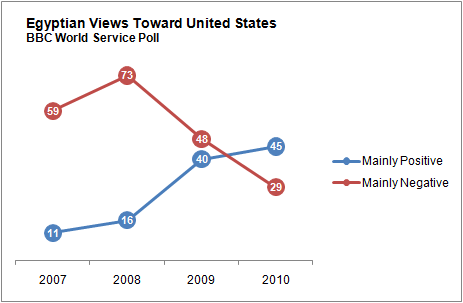

But how likely is that? The chart above, from Nate Silver via Andrew Sullivan, is encouraging.

Egyptian popular opinion toward the United States has substantially improved over the course of the past 2 to 3 years, to the point that a new leader would probably not gain any points by expressing anti-American sentiment.The BBC World Service conducts an annual survey in 28 countries, in which it asks participants how they feel about each of the others. The BBC has interviewed Egyptians as part of its survey since 2007.

Egyptian sentiment toward the United States has improved dramatically since the survey began. In 2007, just 11 percent of Egyptians said they viewed the United States as having a “mostly positive†influence, versus 59 percent who said it had a “mostly negative†influence. The numbers were even worse the next year: 16 percent positive, but 73 percent negative.

The election of President Obama created a major change in opinion, however. In 2009, positive opinions about the United States rose to 40 percent against 48 percent negative. And last year — the first survey conducted after Mr. Obama’s well-received June 2009 speech in Cairo — positive opinions became the plurality, at 45 percent, against 29 percent negative views, figures comparable to those for survey participants in the United Kingdom and France.

Whether Obama’s Cairo speech was “well-received” depends on who is doing the receiving, but it seems clear that the replacement of Bush with Obama has had a strong positive effect for American popularity in Egypt. And while other conservatives have found fault with Obama’s handling of the Egyptian crisis, I don’t see much to criticize. This is not the good-versus-evil riots in Iran in 2009, when it took Obama five embarrassing days to unambiguously side with the protesters over a regime that has been at war with us since 1979. Not only is Mubarak a long-standing U.S. ally, he’s not nearly as oppressive as the mad mullahs in Tehran. It makes perfect sense for the U.S. to adopt a neutral stance regarding Egypt.

While the Egyptians may favor Obama over Bush, Bush will deserve some credit for any positive outcome in Egypt. Max Boot:

But whatever happens, one thing is already clear: as Pete Wehner has already noted, President Bush was right in pushing his “freedom agenda†for the Middle East.

When he pushed for democratic change in the region, legions of know-it-all skeptics — including Barack Obama — scoffed. What business was it of America to comment on, much less try to change, other countries’ internal affairs? Why meddle with reliable allies? Wasn’t it the height of neocon folly to imagine a more democratic future for places like Iraq or Egypt?

Turns out that Bush knew a thing or two. He may not have been all that sophisticated by some standards, but like Ronald Reagan, he grasped basic truths that eluded the intellectuals. Reagan, recall, earned endless scorn for suggesting that the “evil empire†might soon be consigned to the “ash heap of history.†But he understood that basic human desires for freedom could not be repressed forever. Bush understood precisely the same thing, and like Reagan he also realized that the U.S. had to get on the right side of history by championing freedom rather than by cutting disreputable deals with dictators.

Hm… Comparing Bush with Reagan… where have I heard that before?

Leave a Reply