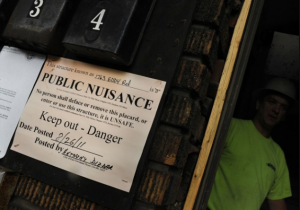

Cleveland, where the Cuyahoga River once caught fire, is a pioneer in what seems to be a productive method for dealing with the wave of foreclosures that have blighted that city and many others. The land bank program described by the Washington Post today involves cooperation between government, non-profits and banks, to the benefit of all parties.

A handful of the nation’s largest banks have begun giving away scores of properties that are abandoned or otherwise at risk of languishing indefinitely and further dragging down already depressed neighborhoods.

The banks have even been footing the bill for the demolitions — as much as $7,500 a pop. Four years into the housing crisis, the ongoing expense of upkeep and taxes, along with costly code violations and the price of marketing the properties, has saddled banks with a heavy burden. It often has become cheaper to knock down decaying homes no one wants.

The demolitions in some cases have paved the way for community gardens, church additions and parking lots. Even when the result is an empty lot, it can be one less pockmark. While some widespread demolitions could risk hollowing out the urban core of struggling cities such as Cleveland, advocates say that the homes being targeted are already unsalvageable and that the bulldozers are merely “burying the dead.â€

Two things about this warm my capitalist heart. One of them is described in the article. Instead of the aimless juvenile antics of the Occupy Wall Street crowd, the land bank program enlists the banks that helped create the mess in the effort to clean it up.

Cleveland has found progress in the sliver of common ground between the land bank’s mission and the interest of financial firms, including some that helped fuel the housing crisis through risky loans and later botched paperwork in carrying out foreclosures across the country.

This collaboration was uncomfortable at first, said Gus Frangos, the Cuyahoga land bank’s president and one of the people behind the state law.

“Two years ago, when we started . . . it was difficult,†he said. “Everybody was guarded.â€

After countless meetings, however, land bank officials and banking representatives shed their initial wariness of one another. Frangos made a simple pitch: We’re not here to point fingers. We’ll take your worst properties, the ones not worth keeping. Pony up for the demolition, and you’ll still come out ahead. Just don’t walk away from them.

And in the process, construction — or destruction 🙂 — workers are employed who otherwise might be idle.

(Photo: Washington Post)